The question you have to ask yourself, White America needs to ask itself: Why was it necessary to have a nigger in the first place? ~ James Baldwin, I Am Not Your Negro

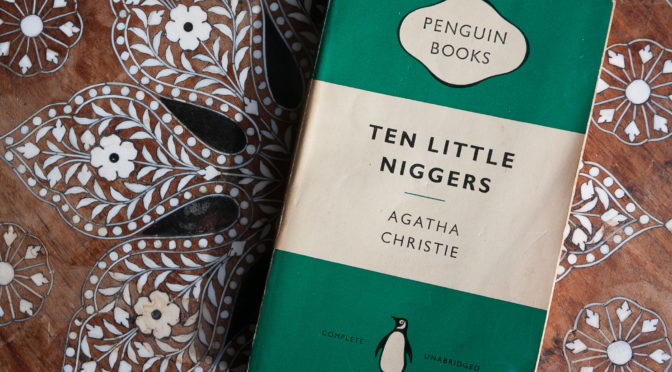

In a neighbouring village more English than England and whiter than white, I found Agatha Christie’s book in the stacks of the church’s charity book sale. I was shocked to a degree commensurate with my liberal leanings. Then I bought it for a dollar.

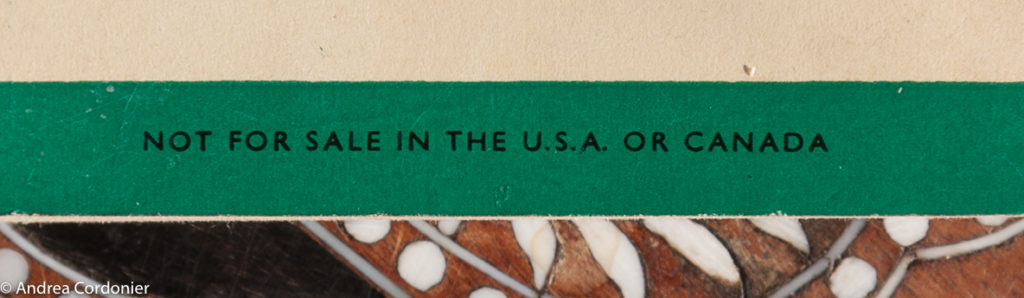

Published in England before the Second World War, the cover of this edition explicitly states that it is “not for sale in the U.S.A. or Canada.” It was later republished as Ten Little Indians – hardly a stellar rebranding – and, finally, as And Then There Were None. It ranks as the 10th best-selling book of all time. ((https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_best-selling_books)) That’s an awful lot of influence.

Before it was a book, it was a popular children’s rhyme with variants and roots in the folk tradition and black-face minstrel shows of Reconstruction-era America.

During Reconstruction in the 1860s, the proud Confederate states found themselves in a place of subordination. Forced to concede their free slave labor, the former citizens of the Confederacy refused to fold their ideology of the inferiority of the freed slaves. A “comic” song titled “Ten Little Niggers” circulated through the United States in Minstrel shows and children’s nursery rhyme books in keeping with this ideology.

…While the purpose of its widespread popularity was to refute the competency and human qualities of the black freedmen to white audiences, the ultimate legacy that the rhyme leaves behind is the mental conditioning of following generations of black males. The white population who circulated the song intended to define the black freedmen as barbaric and ignorant, yet the song also connected the white-constructed definition of ‘nigger’ to the black man’s consciousness. ((https://folkloreforum.net/2009/05/01/“ten-little-niggers”-the-making-of-a-black-man’s-consciousness))

The live performances of Ten Little Niggers in minstrel shows allowed the white audience to face a living manifestation of their fears in comic form. The act of chiding the black race became an empowering act of watching black or blackface performers denounce themselves in a public forum. ((https://folkloreforum.net/2009/05/01/“ten-little-niggers”-the-making-of-a-black-man’s-consciousness/))

And so the rhyme goes:

Ten little nigger boys went to dine; one choked his little self and then there were Nine.

Nine little nigger boys sat up very late; one overslept himself and then there were Eight.

Eight little nigger boys travelling in Devon; one said he’d stay there and then there were Seven.

Seven little nigger boys chopping up sticks; one chopped himself in halves and then there were Six.

Six little nigger boys playing with a hive; a bumblebee stung one and then there were Five.

Five little nigger boys going in for law; one got in Chancery and then there were Four.

Four little nigger boys going out to sea; a red herring swallowed one and then there were Three.

Three little nigger boys walking in the Zoo; a big bear hugged one and then there were Two.

Two little nigger boys sitting in the sun; one got frizzled up and then there was One.

One little nigger boy left all alone; he went and hanged himself and then there was None.

It continues until all ten are dead, attributed to their failure to learn from experience, a lack of competency and poor mental acuity. Black men were considered a danger to others, especially white women, as well as to themselves, therefore requiring a white master to look after them ‘properly.’ A line-by-line interpretation of the rhyme can be found here.

Ten Little Niggers, and other cultural instruments like it, perform the very specific role of indoctrinators for adults and children alike. They validate language and beliefs, drawing them into the mainstream with the false logic that if everybody uses the words or laughs at the jokes, then it must be okay. ((https://folkloreforum.net/2009/05/01/“ten-little-niggers”-the-making-of-a-black-man’s-consciousness))

American literary critic, teacher, historian, filmmaker and public intellectual Henry Louis Gates, Jr.:

So, when a white person confronted an actual black human being, he or she was “an already read text,” to use Barbara Johnson’s brilliant definition of a stereotype in her book, A World of Difference. It didn’t matter what the individual black man or woman said and did, because negative images of them in the popular imagination already existed, as if they were “always ‘in place,’ ” as my colleague Homi K. Bhabha puts it (pdf), “already known, and something that must be anxiously repeated … as if the essential … bestial sexual license of the African [for example] that needs no proof, can never really, in discourse, be proved.” Hence the need to repeat these images over and over again, endlessly. The racist stereotype was subconsciously imposed on the face of an actual African American, the American mask of blackness, and these images justified the rollback of the gains black people had made during Reconstruction. ((http://www.theroot.com/should-blacks-collect-racist-memorabilia-1790896701))

Then, more than 75 years after Agatha Christie’s publication, along came Brexit, with immigration cast in the lead role of scapegoat and untempered racism on open display. Knowing history, it shouldn’t have come as much of a surprise.

At its height, the British Empire was the largest in history and, for over a century, was the foremost global power. By 1913 it held sway over 412 million people, 23% of the world population at the time, and by 1920 it covered 35,500,000 km2 (13,700,000 sq mi), 24% of the Earth’s total land area. As a result, its political, legal, linguistic and cultural legacy is widespread. At the peak of its power, the phrase “the empire on which the sun never sets” was often used to describe the British Empire, because its expanse around the globe meant that the sun was always shining on at least one of its territories. ((https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/British_Empire))

The transfer of Hong Kong to China in 1997 marked for many the end of the British Empire. ((https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/British_Empire))

According to the New York Times, Pro-Brexit advocates have framed leaving the European Union as necessary to protect, or perhaps restore, the country’s identity: its culture, independence and place in the world. This argument is often expressed by opposition to immigration. ((https://www.nytimes.com/2016/06/21/world/europe/brexit-britain-eu-explained.html?_r=0))

So what should I do with the book I bought for a dollar at the church book sale?

Gates offers two options: donate it to a respected collection to facilitate societal critique, so that “our children…know where we have been [in order] to know where we are going.” Or burn it ’til it is no more. ((http://www.pbs.org/wnet/african-americans-many-rivers-to-cross/history/should-blacks-collect-racist-memorabilia))

There is no room for ambivalence, he says, because “it is the force of ambivalence that gives the colonial stereotype its currency.” ((http://courses.washington.edu/com597j/pdfs/bhabha_the%20other%20question.pdf))

************

I Am Not Your Negro, a film written by James Baldwin, directed by Raoul Peck and voiced by Samuel L. Jackson, explores the history of racism in the United States through Baldwin’s reminiscences of civil rights leaders Medgar Evers, Malcolm X and Martin Luther King, Jr.

Premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival in 2016, it is in limited release across the U.S. Check the website or local theatres for dates.