In our family, turning six entitled the birthday child to a five-day trip to New York with Mamma.

It was a mutually beneficial ruse: I enjoyed a big-city adventure roughly every eighteen months and they got my undivided attention and an itinerary to match their interests.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art became a staple. Set on the edge of Central Park on Museum Mile, it is child-centric – without earnestly striving to be so – and offers a gorgeous building containing a near-bottomless reservoir of eclectic man-made miracles.

On that first trip with my eldest son, Dante, we made a beeline for the Arms and Armor Collection, the Egyptian Collection and the European Sculpture Court. What we accidentally discovered was a private study carefully crafted from walnut, beech, rosewood, oak and fruitwoods in the trompe l’oeil style.

Federico da Montefeltro (1422-1482), Duke of Urbino in the Marches, a leading military figure in Quattrocento Italy, was also famous for his knowledge and understanding of the arts. In the palace of his capital of Urbino he created a studiolo, a small room for study, decorated with a lavish wall paneling of intarsia, or precious inlaid woods, that was completed about 1476. The redesign of his palace at Gubbio, following plans by Francesco di Giorgio Martini, also began that year. Once again, Tuscan artists outfitted another studiolo with panels of intarsia. This time they emphasized the duke’s personal devices and such attributes of learning as musical and scientific instruments, skillfully executed from designs of great refinement. (www.metmuseum.org)

When I saw the Studiolo Gubbio I recognized perfection.

I was awestruck and heartbroken, knowing that I could never make anything so creative, intricate and powerful. The Studiolo was not born of a generalist like me, but of three masters of their craft. With flawless execution, the ingenious craftsmen tricked observers into seeing three-dimensional objects where only two existed. When I saw these panels I grasped the overwhelming impulse of humans to possess great works of art and craft. Why would plain walls do when these exist?

The scale of the Studiolo is human, but it has lost its original context like so many other precious and desirable objects cloistered in museums and private galleries. This room was once in a house – albeit a large one – alive with daily activity and usefulness. There is gain for gallery visitors like myself, but there is a measure of loss, too. The Studiolo is no longer animated. Its voices are silent and its lively narrative closed.

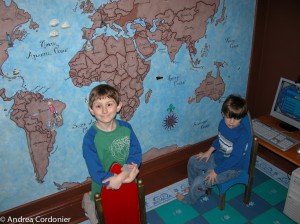

While I could never afford something as precious as the Studiolo Gubbio, inspiration flows freely. We returned home and I set out to create a modest studio for Dante. I painted the floor, panelled the walls, created a Greek alphabet frieze, and painted a magnetic wall map of the world. There he strategized battles and moved his ships and explorers to the far corners of his imagination.

The look on his face while he played? Priceless.

More images and history of Studiolo Gubbio are available here.