[pullquote]Emily Carr (December 13, 1871 – March 2, 1945) was a Canadian artist and writer heavily inspired by the Indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest Coast. ((http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Emily_Carr)) [/pullquote]

A moment’s quiver of homesickness for Canada strangled the Art longing in me. To ease it I began to hum, humming turned into singing, singing into that special favourite of mine, “Consider the Lilies.” Whenever I let that song sing itself in me, it jumped me back to our wild-lily field at home. I could see the lilies, smell, touch, love them. I could see the old meandering snake fence round the field’s edge, the pine trees overtop, the red substantial cow, knee-deep and chewing among the lilies. ((Growing Pains: “Nellie and the Lily Field”, pp. 49))

By the time I tour Emily Carr’s childhood home the spring glory of Victoria’s wild lilies is long gone. The enclosed field she affectionately recalls is ancient history, having succumbed to the pressures of development and the need to sell off land to support a growing family. The old house in the Italianate villa style, built in 1863 and now fully restored as a museum and event space, sits on a fraction of its original ten acres. Many respected and wealthy families eventually built in the neighbourhood, but in the beginning, when the Carrs arrived from England via California, it was wilderness.

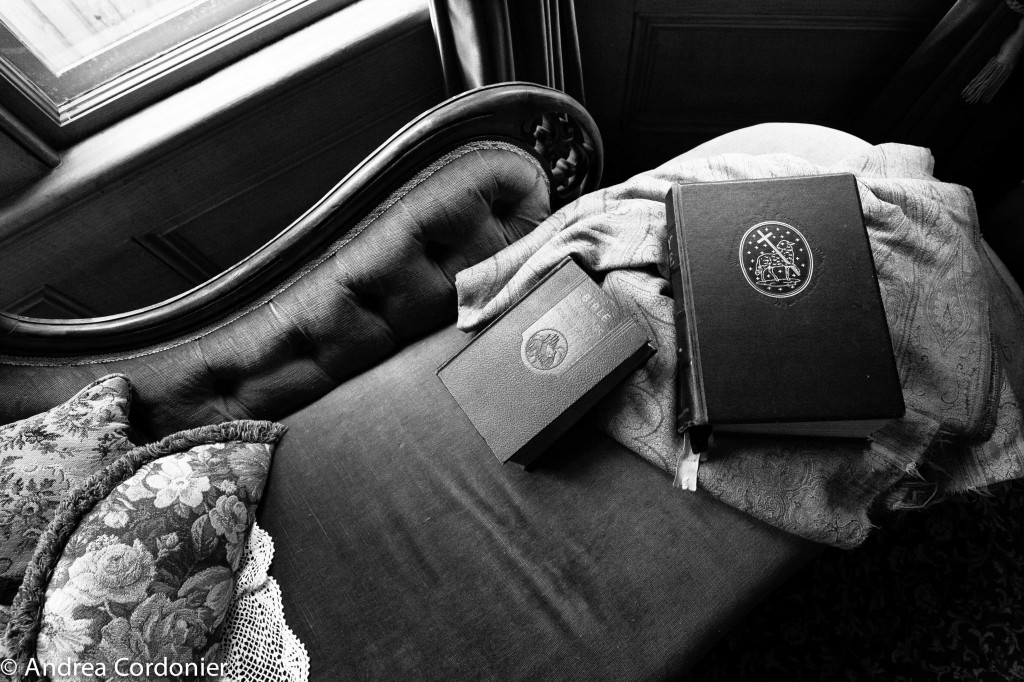

Emily was the youngest of nine children, frequently grouped with her two youngest sisters and separated from the elder girls by the death of three brothers and a two-decade age gap from top to bottom. Her father, Richard, was a Presbyterian who ruled with a heavy bible and iron fist. Rigid piety filled the place where his heart might have been. Her mother, Emily Sr,. acted as counterweight as best as she could, but society was patriarchal, conservative, and, in Victoria’s case, striving to be “more English than England.” Her mother died when Emily was twelve and her father two years later. Her eldest sister, Edith (Dede), took over the reigns as head of household and life at home became unbearable.

…life at home was neither easy nor peaceful. Outsiders saw our life all smoothed on top by a good deal of mid-Victorian kissing and a palaver of family devotion; the hypocrisy galled me. I was the disturbing element of the family. The others were prim, orthodox, religious. My sister’s rule was dictatorial, hard…I would not sham, pretending that we were a nest of doves, knowing well that in our home bitterness and resentment writhed. We younger ones had no rights in the home at all. Our house had been left by my father as a home for us all but everything was in big sister’s name. We younger ones did not exist. ((Growing Pains, pp. 34))

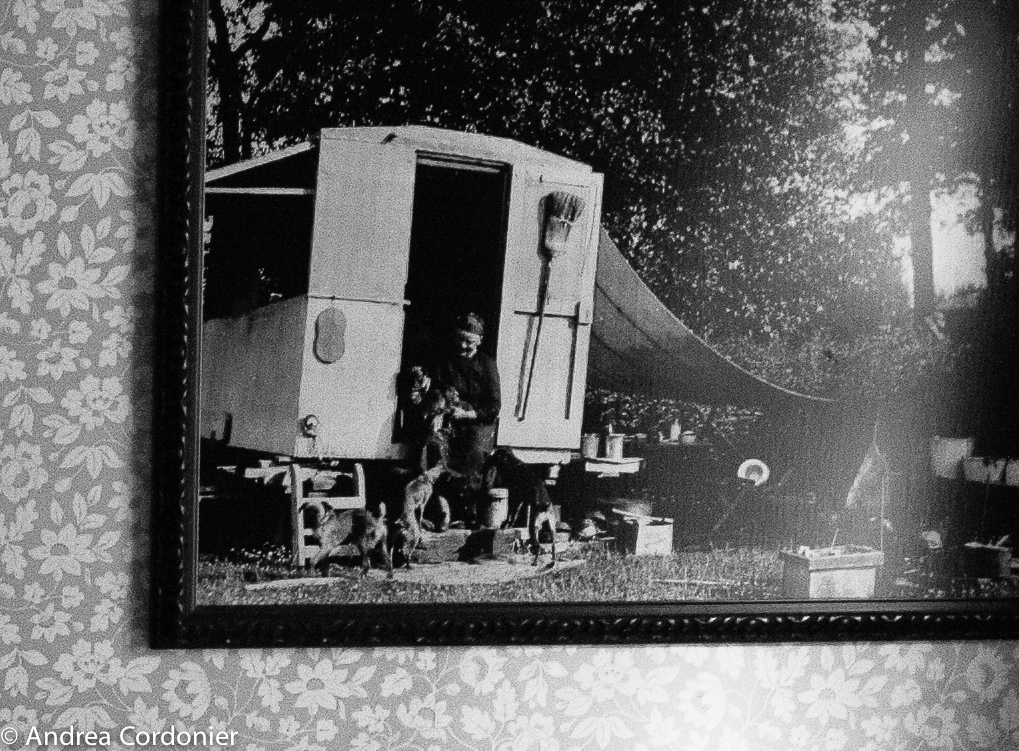

Emily found solace in the family’s barnyard animals and other wild creatures that roamed the property. She escaped the crushing social mores of “townies” on the back of her ex-circus pony, Johnny, pushing deep into the silent woods. At sixteen she secretly solicited permission and modest financial support from the family’s legal guardian and set sail for art school in San Francisco. When she was called home to begin “serious work” she gave art lessons to children, and accompanied a missionary to Ucluelet for her first immersive – and formative – experience with Nuu-Chah-Nulth culture. A French painter and his wife came to Victoria to work but, disappointed with the scenery, they hurriedly returned home. Emily was again left without peers.

[pullquote]Artists from the Old World said our West was crude, unpaintable. Its bigness angered, its vastness and wild spaces terrified them. ((Growing Pains, pp. 107))[/pullquote]

To advance her studies she moved to London and Paris and was plagued by crippling health issues. Her physicians said that Canadians never fared well in the crowded, dirty cities of the Old World. Emily returned home to the wild spaces of British Columbia but home exacted a terrible price: Her work was roundly denounced. Unable to earn a living from her art, she stopped painting for fifteen years as she built her House of All Sorts and let rooms to make ends meet.

She was born in the right place at the wrong time, a pioneer of modernist painting stuck in an artistic backwater. It would be decades before she would find her creative tribe and literary/artistic success.

Further reading:

3 responses to “Literary Houses: Emily Carr”

Loved this, Andrea. Carr was, and still is, a muse for me. (When I was about 20, I realized she helped to shape the way I see the forests around me.) My daughter volunteers at Ross Bay Villa in Victoria and one of the projects she worked on was the floor cloth. You can see it here (also the faux wood panelling she also helped with): http://toadhollowphoto.com/2014/02/14/ross-bay-villa-falling-love-history/

Thanks, T. You had posted about Ross Bay Villa before and it was in the back of mind to stop by for a tour during our trip. As usual, not enough time and a balance of needs to consider beyond my own! The floorcloth and wall coverings are gorgeous. The trompe l’oeil woodwork is amazing; it is work requiring both considerable skill and patience and your daughter obviously has both. Emily Carr has been a surprise for me. Until I went in search of her paintings I had no idea she wrote. I LOVE her crisp prose, her directness, the activeness of the work. Reading her is reading first-person adventure which I find particularly satisfying. In my eyes, she is heroic. Looking forward to writing more about her.

Yes, her writing is marvellous. The conservator who is responsible for designing that floor cloth at Ross Bay Villa is Simone Vogel-Horridge. She’s amazing. If you go to the Villa’s website — http://rossbayvilla.org/ — you can see some of the work she’s spearheaded. The volunteers — Angelica is just one of many — are very dedicated and a tour of the Villa is a great experience.