Reading to children is inextricably intertwined with the idea of home, comfort and love. These five children’s books by authors better known for their adult writing, are available in first edition form from Peter Harrington, London’s leading rare book firm. And because we all love a good backstory, the home lives of the authors prove as interesting as the books themselves.

This piece is reproduced with permission from its author, Rachel Chanter, and Peter Harrington Rare Books.

It is, perhaps, rare that an author can turn their hand with equal success to both children’s and adult literature. Indeed, many have no wish or intention to write for younger readers: see, for example, Martin Amis’ contentious claim a few years ago that to pen a work of children’s literature would be to write at “a lower register than what I can write”. Children’s writers were quick to counter Amis’ statement by pointing out that writing for younger readers requires as much research, complexity and inventiveness as it does for the adult market. “Children are astute observers of tone – they loathe adults who patronise them with a passion, adults who somehow assume they are not sentient beings because they are children” said children’s author Lucy Coats in response.

A number of extremely well-known authors have successfully vacillated between age groups in their published works. J. K. Rowling’s visceral crime novels, written under the pen name Robert Galbraith, retain the intelligence, sensitivity and well-executed pacing of the Harry Potter series whilst allowing her to exercise her not-inconsiderable capacity for the macabre with more freedom. In contrast, the Ian Fleming who wrote Chitty Chitty Bang Bang for his son Caspar is not immediately identifiable as the creator of James Bond, yet his children’s story is almost as well-known and iconic as his gentleman spy – a state of affairs which has come about in no small way through the success of the musical, adapted from the novel by none other than Roald Dahl. Dahl himself slipped seemingly effortlessly between genres, using his occasionally cruel sense of mirth at the grotesque to shock and delight child and adult readers alike.

There are, in fact, a surprising number of well-known writers, the success of whose work for adults has almost entirely eclipsed their contributions to the field of children’s literature. These lesser-known works, however, can often lend an interesting new perspective to our knowledge of their creators, as well as being engaging discoveries in their own right. We have chosen a few of the most interesting to explore.

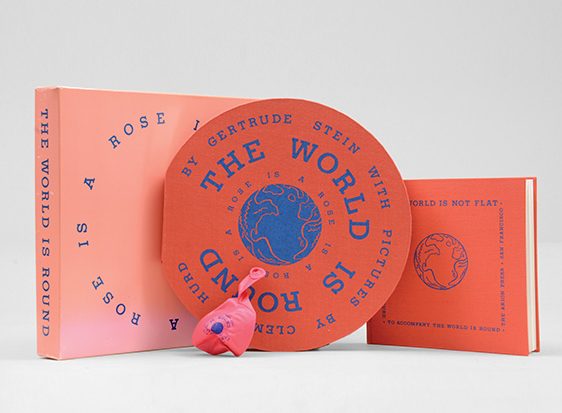

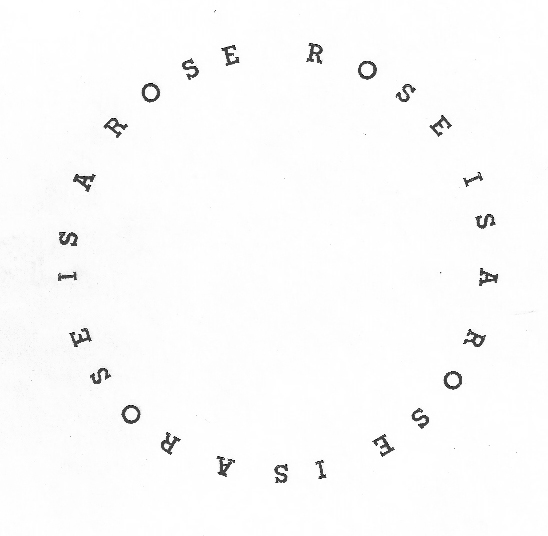

Gertrude Stein – The World is Round (1939)

Known by many as the epicentre of the modernist movement which congregated around her Parisian salons, those who have heard of Stein in connection with her children’s book, The World is Round, likely constitute a significantly smaller group. However, in 1938, Margaret Wise Brown, editor of the newly-formed Young Scott Books, was embarking on a project which invited leading contemporary authors to try their hand at writing for children. Whilst the likes of Ernest Hemingway and John Steinbeck declined, Stein surprised Brown by replying that she had an almost-completed children’s manuscript which she would like them to publish. This was by no means an uncomplicated process: Stein had a very clear vision for the book, specifying that it must be printed in blue on pink paper and naming Francis Rose, with whom she had previously worked, as her preferred illustrator. The publisher obliged on the first count but required Stein to select an illustrator of their recommendation, fearing that Rose’s drawings would not appeal to children. Clement Hurd, who would go on to illustrate Brown’s own popular children’s book Goodnight Moon, was eventually chosen, although Stein deemed his work to be merely “sweet but very undistinguished…”

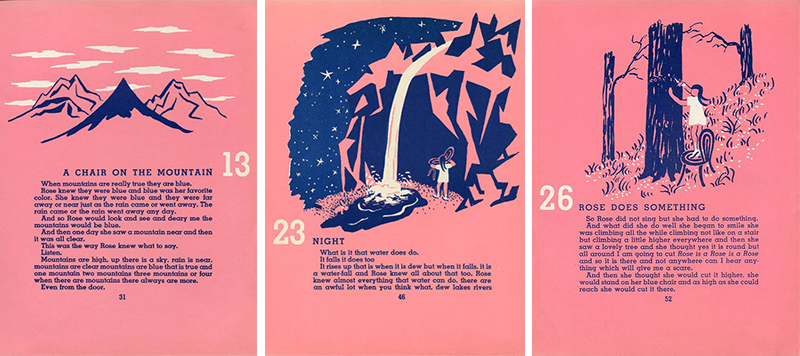

Stein’s book is a strange and lyrical mix of largely unpunctuated prose and poetry which explores the relationship between words and meaning, and a child’s sense of their own identity. The protagonist Rose constantly questions herself and the world around her whilst, in contrast, her cousin Willy is self-assured and uninquisitive. The narrative is built around Rose’s journey to the top of a mountain where she feels she will discover some surety. Whilst travelling alone through a forest, she is frightened by her solitude and decides to carve her own name into a tree as a restatement of her identity. She ends up carving ‘Rose is a Rose is a Rose…’in an endless ring, an echo of Stein’s most famous line which is repeated in differing iterations in several of her works and can be said to encompass her central ideology: that things are as they are.

The World is Round received mixed reviews, with some criticising the impenetrability of its language and plot, and judging its existential theme to be inappropriate for the age group it was aimed at. Others, however, noted that its rhymes and rhythms were sympathetic to the imaginations of young children and that, when read aloud, the plot was actually fairly simple and easy to follow.

The first trade edition was issued alongside 350 special signed slipcase copies. It was reissued by Young Scott in 1966 and Hurd took the opportunity to revise or replace several of his illustrations which subtly reinterpret the text. In 1986, the book was chosen for reissue by Arion Press in a limited edition round volume, accompanied by a separate volume, The World is Not Flat – an essay on the history of the book written by Hurd’s wife Edith Thatcher Hurd (from which much of the above information is drawn).

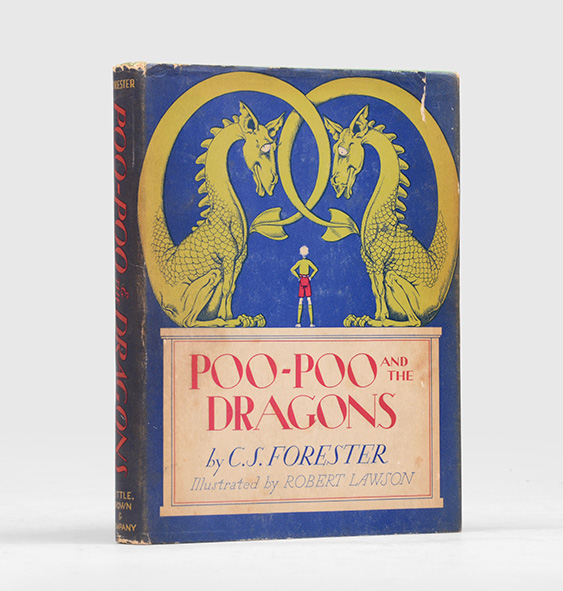

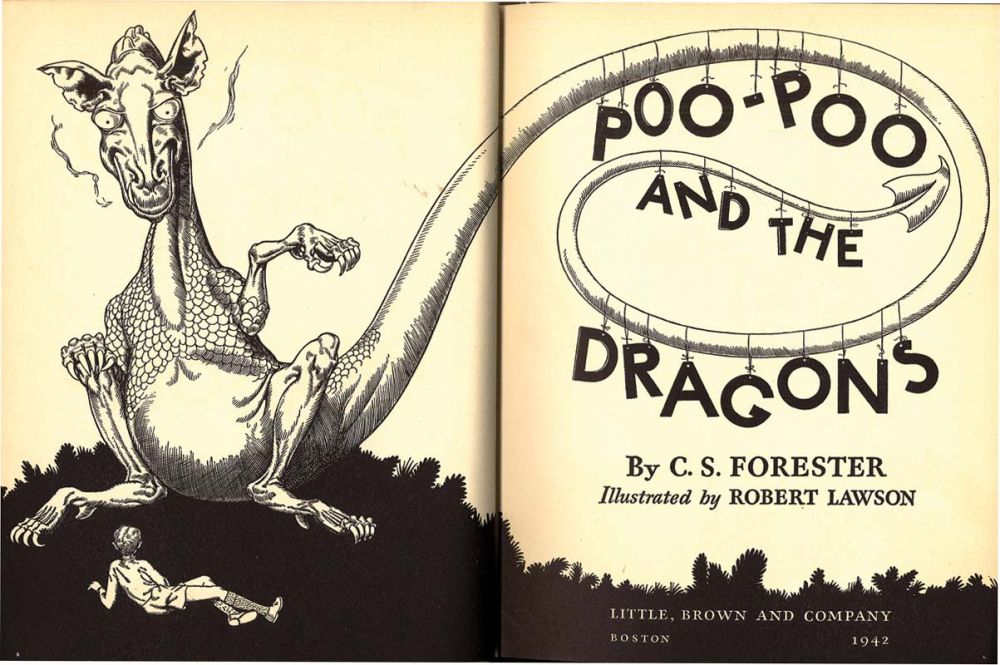

C. S. Forester – Poo Poo and the Dragons (1942)

Beloved of Winston Churchill and Ernest Hemingway, C. S. Forester’s Napoleonic war hero Horatio Hornblower is what literary history best remembers him for. Forester, however, was a versatile writer, publishing two crime novels, The African Queen – which was turned into the extremely successful movie directed by John Huston – and two books for children.

Poo Poo and the Dragons began life as a series of stories Forester would tell to his two sons at mealtimes. The younger of the two boys, George, would often refuse to finish meals, particularly when his mother was away. To get him to finish his food, Forester would tell stories about the little boy Poo Poo and his adventures with his mischievous dragon friends. If George stopped eating, Forester would stop the story mid-sentence. His stories became so enthralling, however, that George’s eating troubles vanished and Forester found himself unable to eat his own dinner in the face of his avid listeners. He then began asking his sons to come up with names for each new character, and wouldn’t begin telling the story again until a suitable name had been devised, giving him time to wolf down some of his own food.

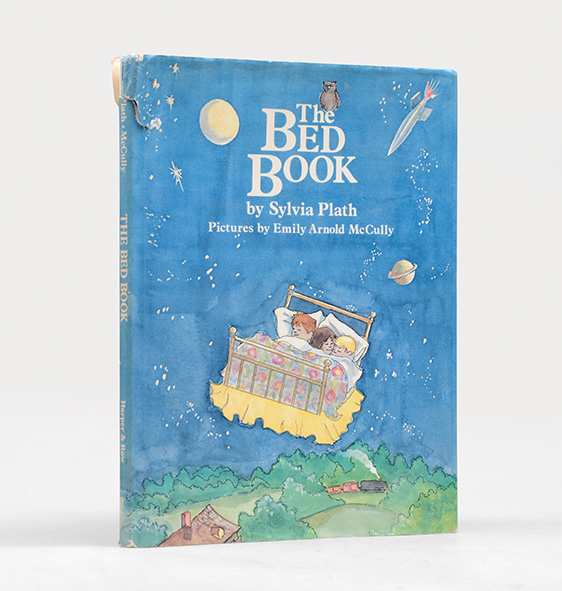

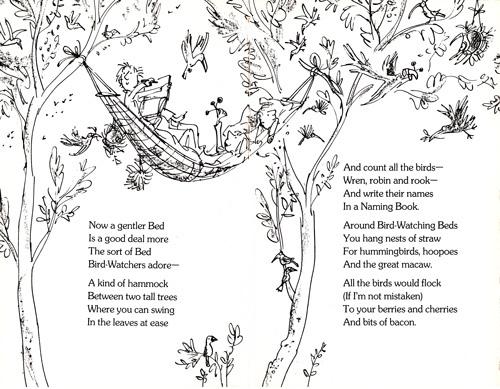

Sylvia Plath – The Bed Book (1976)

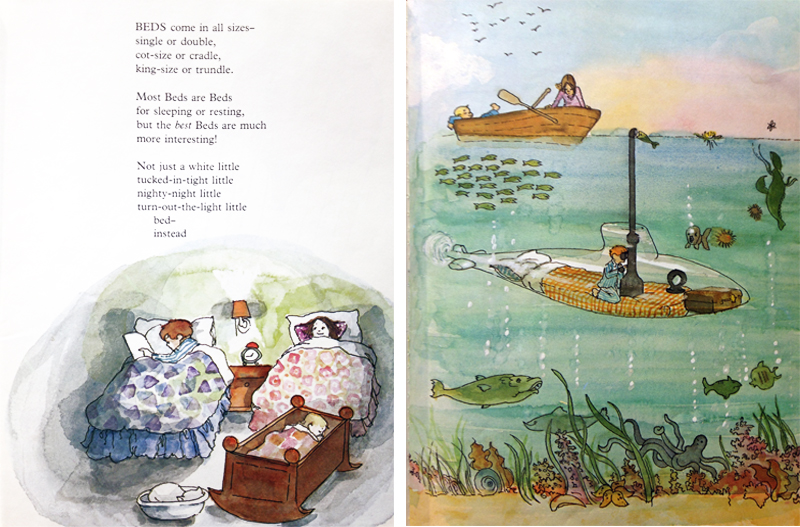

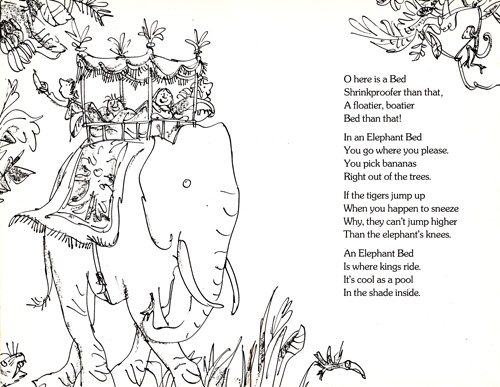

Perhaps the patron saint of writers whose tragic life stories have overshadowed a nuanced appreciation of their work, Sylvia Plath’s playful and inventive children’s fiction throws a welcome light on her broad range as a writer. The Bed Book is a charming poem which posits a series of fantastical beds – ‘A Bed for Fishing, / A Bed for Cats, / A Bed for a Troupe of Acrobats’ – and was written when she and Ted Hughes were trying for a baby in 1959.

Whilst its subject matter may seem miles away from the work on which her reputation as a poet of depression and suicide is based, The Bed Book exemplifies Plath’s great sensitivity for language and rhyme, and for presenting the ordinary in an extraordinary and arresting manner. The sense of building euphoric energy can be likened to the joyful overflow of some of her Ariel poems, which bring to vivid life a house animated by her children. Like her other children’s works, The It-Doesn’t-Matter-Suit and ‘Mrs Cherry’s Kitchen’, The Bed Book turns the domestic space into a fantastic one, and communicates to us a little of Plath’s conception of the happiness of an ideal home. Critics have considered Plath’s work for children alongside her others which centre on home life, and which place women in fairly conventional roles within it, drawing attention to her conflicting allegiance to feminist ideologies of 50s and early 60s and her idealised image of the traditional domestic setup. Her children’s literature may even give us an interesting perspective on the despair that ensued on the later disintegration of her own home and marriage.

Plath wrote in her journal for May 3rd 1959:

I wrote a book yesterday. Maybe I’ll write a postscript on top of this in the next month and say I’ve sold it. Yes, after half a year of procrastinating, bad feeling and paralysis, I got to it yesterday morning, having lines in my head here and there, and Wide-Awake Will and Stay-Uppity Sue very real, and bang. I chose ten beds out of the long list of too fancy and ingenious and abstract a list of beds, and once I’d begun I was away and didn’t stop till I typed out and mailed it…

Sadly, The Bed Book didn’t appear in print until 1976, thirteen years after her death. The first UK edition was illustrated by Quentin Blake and is now extremely hard to come by. Though she did not live to see this delightful creation in print, Plath’s diary entry echoes some of the exuberant spirit in which it was composed, though it also hints at the darker side of her nature: “Funny how doing it freed me. It was a bat, a bad-conscience bat brooding in my head…”

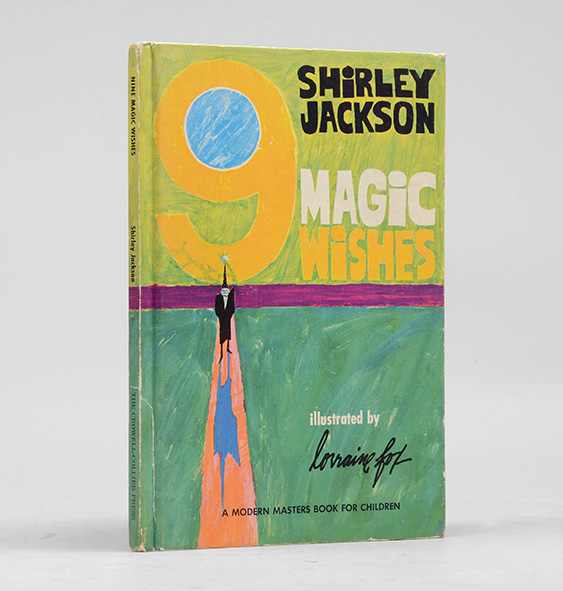

Shirley Jackson – Nine Magic Wishes (1963)

Anyone who has trembled their way through The Haunting of Hill House will know that the sensations of abject terror have rarely been transmogrified into literature with such consummate skill. Similarly chilling, her final novel, We Have Always Lived in the Castle, does the work of a supernatural thriller without a ghostly apparition in sight. Jackson’s fiction is full of unloved daughters, slippery narrators and the sense of walking on the precipitous edge of imminent catastrophe and mental collapse. Whilst she also penned a successful side-line of sunny accounts of motherhood and domestic life, an occasional sharp edge of dissatisfaction peeps through the light-hearted prose. These books are thrown into a rather sinister light when one considers Jackson’s later alcoholism, agoraphobia and addiction to painkillers, brought on by an unhappy home life. So it is with slight trepidation, perhaps, that one might contemplate what guise her work for children might take.

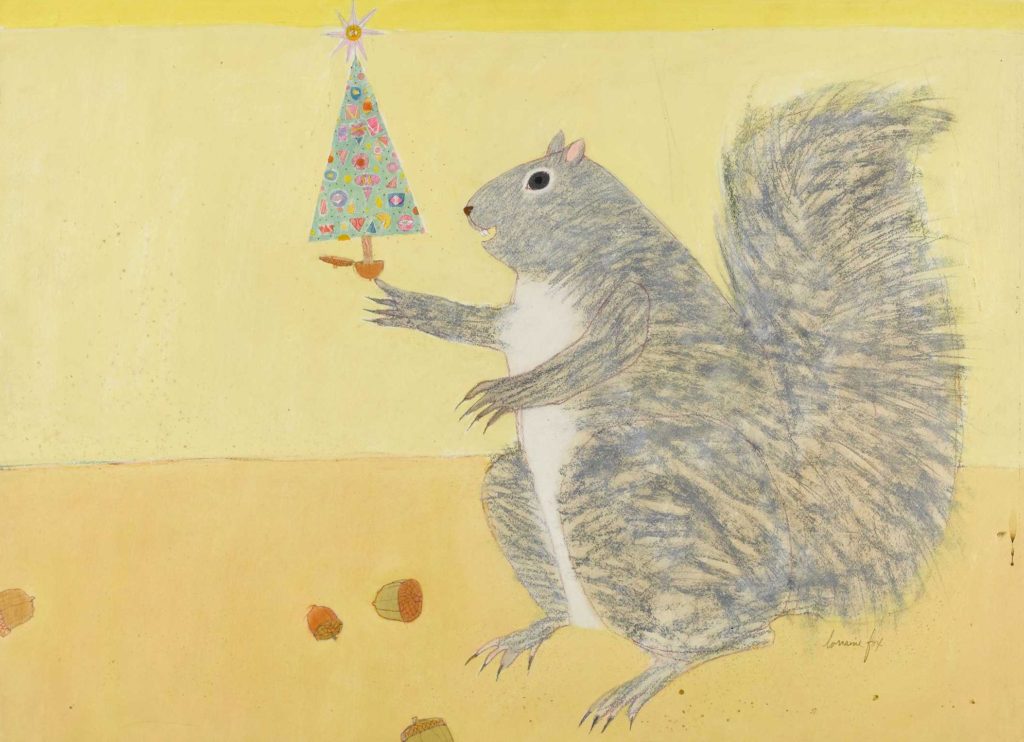

9 Magic Wishes, however, is a relatively conventional, if slightly enigmatic, children’s picture book which tells the story of a little girl who is visited by a wizard. Despite its relative simplicity, though, it is not without the qualities which led novelist Johnathan Letham to call her “one of this century’s most luminous and strange American writers”. Its opening line – “Today was a very funny day. The sky was green and the sun was blue and all the trees were flying balloons” – is typical of Jackson’s talent for slightly uncanny settings, even in the absence of haunted houses or forbidding parochial towns. The little girl’s wishes that are granted by the wizard are curious and enchanting: “an orange pony with a purple tail”, “a squirrel holding a nut that opens and inside is a Christmas tree”, “a little box and inside is another box and inside is another box and inside is another box and inside that is an elephant”.

Jackson was given by her publisher what she referred to as an “arrogant little list” of basic vocabulary she should confine herself to, and which was felt to be instructive to new readers. It included “getting” and “spending”, “cost” and “buy”, “nickel” and “dime” but no mention of magic. It is testament to her quiet tenacity that she clearly threw this list out completely. She later wrote

I felt that the children for whom I was supposed to write were being robbed, persuaded to accept nickels and dimes instead of magic wishes. This is a very small quarrel; there are many groups of educators who feel that Fairyland is an unhealthy environment for growing minds, but in a choice between television (“television” was on the list) and Fairyland, I know where I would rather have my own children growing up.

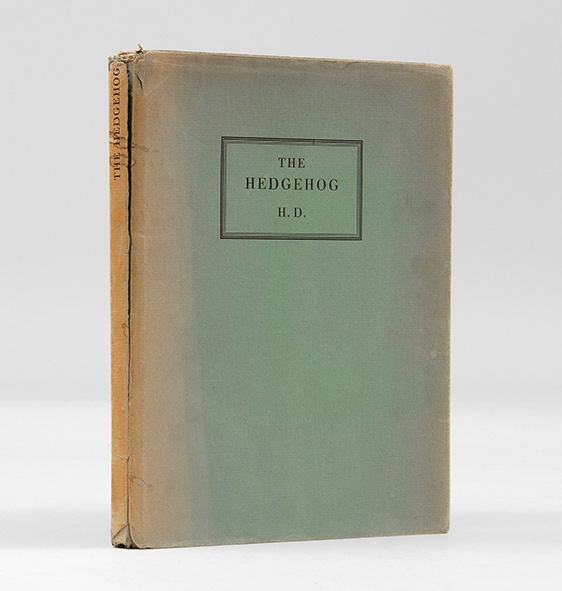

(H)ilda (D)oolittle – The Hedgehog (1936)

Hilda Doolittle (known by the moniker H. D., given to her by literary champion Ezra Pound) cannot perhaps be called a well-known writer, even for an adult audience. However, her children’s offering, The Hedgehog is of sufficient interest and curiosity to merit inclusion in this list. Historically, H. D. has been most often mentioned in the context of the short flurry of magazines, manifestos and anthologies the constituted the avant-garde Imagist movement. In reality, however, her talents extended far beyond the circumscribed literary persona of Pound’s Imagiste paragon, and her work has been adopted by feminist and gay rights movements and has grown in popularity since the 1970s. Her influences from Classical Greek literature and her arrestingly sparse poetry have led some to hail her as a modern Sappho, whilst her autobiographical novels deal with such knotty themes as the patriarchal culture of literature and bisexual desire.

H. D. led a tempestuous personal life, moving between intense friendships and affairs, and from place to place, with alacrity. Her daughter, Perdita, was brought up in a household that included H. D.’s lifelong companion and sometime-lover, Winifred Ellerman, known as ‘Bryher’ and Bryher’s successive husbands, Robert McAlmon and Kenneth Macpherson (both of whom were also H. D.’s lovers). The Swiss setting of The Hedgehog recalls the time they spent there, on and off, during Perdita’s adolescence. In her introduction to the 1988 reissue of the book, Perdita recalls her mother mentioning the manuscript of a children’s book she was working on intermittently as “a story, well not exactly a story, too long, not exactly a novel, too short. A little book for children set in Switzerland, no not really for children, but about a child…” The story concerns a mother and daughter, loosely based on H. D. and Perdita themselves, and their relationship. Ostensibly a tale about the daughter Madge’s misadventures whilst making her way to a neighbour’s house to obtain a hedgehog that will chase adders from their garden, the books dwells largely on themes that were close to H. D.’s heart: the transmission of knowledge from mother to child, the universal didactic power of myth and her pacifistic sentiments. It is a subtle story, perhaps too obscure in parts for younger children, but which distils the experience of childhood and its complicated transition into adulthood with great verisimilitude.

The book was never intended by H. D. for wide circulation, and only 300 copies were originally published (of which this is one) by The Brendin Publishing Company, a firm owned and privately subsidised by Bryher and others. The illustrator, George Plank, was one of their circle which included Pound, William Carlos Williams and Marianne Moore. Plank was best-known for his fashion illustrations. His style became popular, although he disliked the fashion world and preferred commissions such as The Hedgehog, which allowed him to work from his beloved Sussex cottage. Perdita took three copies of the original three hundred. “I wonder what became of the other 297, and whether any were read by children” she muses. Its reissue by New Directions in 1988 hopefully increased the chance that this unusual book might find its way into the hands of an appreciative young reader.

Other children’s books by well-known authors include:

Umberto Eco – The Bomb and the General (1989)

Graham Greene – The Little Fire Engine (1950)

– The Little Horse Bus (1974)

Salman Rushdie – Haroun and the Sea of Stories (1990)

E. E. Cummings – Hist Whist (1989)

John Ruskin – The King of the Golden River (1932)

T. S. Eliot – Old Possum’s Book of Practical Cats

Ted Hughes – The Iron Man (1968)

Russell Hoban – The Mouse and his Child

Edith Sitwell – Children’s Tales (1920)

Robert Louis Stevenson – A Child’s Garden of Verses (1885)

Ralph Steadman – Jelly Book (1967)

2 responses to ““Too fancy and ingenious”: Children’s Books by Adult Writers”

Love this, Andrea. And important not to let the older books go quiet.

Hi T –

Wish I could afford to buy the first editions for my kids as investments! But settling for finding newer copies for my own reading pleasure. xoxo