And I thought how like these chimes

Are the poet’s airy rhymes,

All his rhymes and roundelays,

His conceits, and songs, and ditties,

From the belfry of his brain,

Scattered downward, though in vain,

On the roofs and stones of cities!

For by night the drowsy ear

Under its curtains cannot hear,

And by day men go their ways,

Hearing the music as they pass,

But deeming it no more, alas!

Than the hollow sound of brass.

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow – from Carillon, 1845

*********

Every Sunday at 9:00am, some blessed soul pulls the rope to ring the bell at the tiny Anglican church at the top of our street, gathering the congregation. On midsummer days the doors are thrown open and voices, raised in prayer and song, fill the streets and laneways, float across the Rideau River, trailing off somewhere past the community hall.

Regardless of what I’m doing, the pealing bell stops me in my tracks to listen, absorb and reflect. Call it what you will – Pavlovian reflex, a vestige of faith, or an exercise of the collective unconscious – but I am called and I respond.

I miss the soundscapes of Western Europe where tower bells figure prominently in the minutia of daily life. I miss the rhythmic regularity that keeps me awake for the first night or two after a transatlantic time change before dissolving into the background.

Like the tourists who flock to Ottawa to expressly admire this jewel in the crown, I am attuned to the Peace Tower Carillon because I live in the country and rarely hear it. I imagine that those working on, or very near, Parliament Hill have ceased to hear it at all, although the Dominion Carilloneur, Dr. Andrea McCrady, plays more than 200 lunchtime concerts a year. She is “the live human being giving expression to the tower.” ((http://music.cbc.ca/#/blogs/2012/4/The-Peace-Tower-Carillon-Canadas-most-iconic-instrument))

Dr. McCrady plays for fifteen minutes each weekday, extending her performance to an hour during high tourist season. The automated Westminster Chime marks the quarter hours, and is turned off and on by the press of a button at the beginning, and end, of each concert.

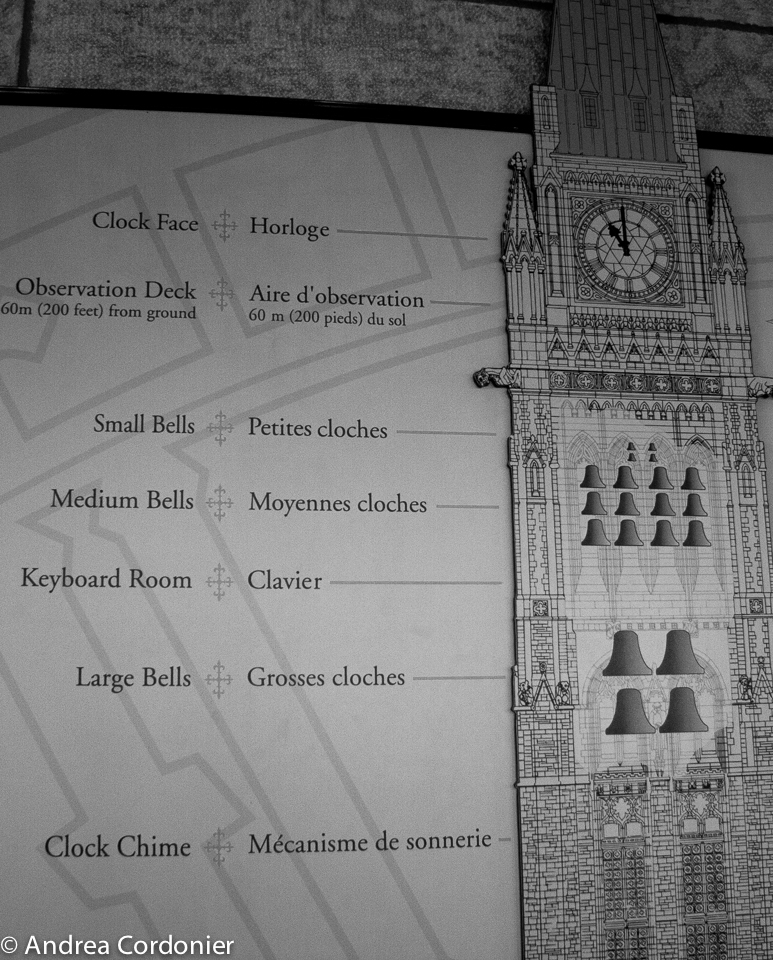

She plays in the confines of the Keyboard Room, midway up the tower, hovering above the largest six bells and below the 47 smallest. We are an audience of three on this spring equinox, and McCrady’s musical selections are appropriately thematic. My friend, Andrea Hossack of the National Arts Centre Orchestra, and I join Piet Chielens of the In Flanders Fields Museum in Ypres, Belgium, a museum dedicated to the study of World War I. I don’t fully appreciate the coincidence until later. Belgium is the birthplace of the carillon and Dr. McCrady will be playing there in June. The Peace Tower was built to honour the 1918 Armistice and the soldiers of the Great War, and the bells of the carillon give voice to the fallen.

Unlike the audience at street level, she (and we) cannot hear what she plays; the music must be piped into the room via external speakers.

The wall clock counts down to noon as Dr. McCrady changes into a pair of soft-soled jazz shoes, adjusts the bench and turnbuckles, and arranges the pages on the ledge of the carillon, all the while recounting the history of the instrument, tales of the parliament buildings, and her experience playing around the world. At the stroke of twelve, she curls her fingers into loosely closed fists, adjusts her position, and launches into O Canada.

Playing the carillon requires a certain vigour. Dr. McCrady slides side to side on the bench, feet dangling above the pedal keyboard, which controls the largest bells, including the 10,000-kilogram bourdon. Her hands and feet apply pressure to the baton-like keys as required, alternating between smooth, gentle depressions and muscle-flexing force. Each piece contains a fury of movement, followed by a brief pause as she switches up the selection. At the end, we are each permitted to sound the bourdon, taking part in a magical ritual that is hidden in plain sight.

For such a large set of bells, the carillon serves a spatially limited audience. Until 1973, restrictions limited the height of buildings in the city’s core to 45.5 metres, well below the 92.2 metre tower, so that the Peace Tower would continue to dominate the skyline. Since that time, building height and density creep have impacted the viewscape as well as the range of the bells. The carillon is best heard from one of three locations: the front lawns of the Parliament Buildings; the west-side patio of the Chateau Laurier; or the parking lot on the north side of the Supreme Court of Canada. The concerts cannot be heard much past the Sparks Street Mall and, as the back of the tower is blocked, they fail to reach across the river to Gatineau.

In the elevator, I ponder my ignorance. I’ve lived in Ottawa for 15 years, so how could I have not known about the concerts? According to Dr. McCrady, most people don’t know she exists.

Is Longfellow right, then, that the dreamy music of the belltowers of this world fall most often on (tone) deaf ears? Prime Minister Robert Borden called the Peace Tower carillon “the Voice of a Nation” and I hate to think that such a powerful instrument and cultural artifact is anachronistic, ignored, there solely for the transient pleasure of tourists.

I hope that we’re not so tuned out to our layered soundscapes, but have instead absorbed such expressive sound on a deeper level, profoundly adding to the subconscious richness of our daily experience.