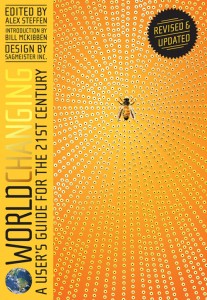

I’m sorry to say that the WorldChanging organization, journalist Alex Steffen’s baby, is no longer with us. There were plenty of interesting and useful postings around sustainability from contributors and the exchange of ideas between readers was smart and thoughtful, which can be hard to find in cyberspace. While it doesn’t specifically focus on shelter, I am posting, in its entirety, one of Alex’s rants from a year and a half ago that continues to give me pause. The select bolding is mine and, of course, all rights remain with WorldChanging. This post reflects my own desire this year to identify and define the best use of my time for the next ten (or forty) years vs. taking off down a path that has the appearance of utility. I have included my response to that post. The WorldChanging archives are still live for the moment and an updated version of the excellent WorldChanging book is available through the website at www.worldchanging.com.

I look forward to continuing this conversation in some form.

*****************

The Revolution Will Not Be Hand-Made: A Quick Sunday-Morning Rant by Alex Steffen, Worldchanging http://www.worldchanging.com/archives/010691.html

(A first stab at articulating some ideas. Thoughtful feedback welcome.)

We’re nearing an inflection point in our discussions about sustainability and building a bright green future.

Mainly, this is because we’re realizing that our task is larger and more pressing than we thought even a few years ago. It’s not enough to be less destructive, to be more sustainable. We need to actually start being non-destructive, being as close to sustainable as we understand how to get. And we need to do it quickly. As Dana Meadows said, in an era where we seem to be running hard up against the limits of so many natural systems, the ultimate limit turns out to be time. If we don’t make truly massive shifts in the next decade or so, we’re committing ourselves to huge troubles; if we here in the developed world don’t transform ourselves in the next two decades, we’re committing ourselves and our descendants to catastrophe.

Given how far we need to go, how quickly (I think we need — for reasons I’ll explain in another piece — about a 95% reduction in our impacts in the next two decades), we can’t waste time on what doesn’t work. We’re being forced, I think, to look at our solutions with a colder eye and clearer judgment. What works? What scales? What has the best political chances of happening? What can make money or creative infectious behavioral change or in some other way self-replicate? What solutions, in short, could work?

Everything else — all the solutions that don’t make that cut — are at best distractions, and in our current situation, where we’re fighting in the public debate for mindshare for real change (and change-stalling propaganda surrounds us), even distractions are not incidental. The idea that every small step is a good thing is simply wrong.

We have inherited a whole set of solutions by conventional wisdom, many of them surrounding lifestyle choices. Almost all of us believe that someone who buys local food, who drives a hybrid, who lives in a well-insulated house, who wears organic clothing and who religiously recycles and composts and avoids unnecessary purchases is living sustainably.

They are not. As we’ve explored a bunch of times in different ways here on Worldchanging, the parts of our lives that actually fall within our direct control are the tips of systemic icebergs, and often changing them does nothing to alter those systems: not individually, not in small groups, not even in larger lifestyle movements. If we’re going to avoid catastrophe, we need to change those larger systems, and change them for everyone, and change them quickly.

It’s quite clear that some of the “solutions” we embrace don’t actually motivate people to change at all. There’s hard evidence suggesting that most of the time, small steps do not actually motivate people to later take larger steps (most people adopt a small change or two and then feel they’ve done their part and stop).

Other times, we ask people to pay attention to the wrong things. Though the efforts some contrarians’ make to discredit local food verge on the absurd, the fact remains that food miles are not the most important measurement of food system sustainability. Perhaps more importantly, some observers’ suggest that local food often serves as a substitute for systemic engagement in movements to change agricultural systems at the largest levels, and I think there’s truth there. Certainly, many of us have a tendency to engage in iconic consumption, without really examining the entirety of our impact and whether our time and money might best be spent trying to effect change in some other way.

That’s not to say that its wrong to garden or recycle or buy CFLs. It’s not. It’s never wrong to try to live a life that’s internally consonant with the change we want to see in the world. Most of those life choices also make us healthier, happier and better off in the long run. So no harm in doing them (disclosure: I garden, recycle and use CFLs). Some personal choices, like forgoing beef and living without a car, not only create some measurable impact, they’re also public enough to signal your beliefs. But we still shouldn’t mistake these things for creating sustainable systems. Until we have systems that reduce the numbers of cows and cars we all use, we’re not making any real progress at all.

We can no longer afford to mistake the symbolic for the effective, or put our hopes in the mystical idea that if enough of us embrace small steps, our values will ripple mysteriously out through the culture and utterly transform it. We’ve been saying that for more than 40 years [NB: see my recent blog on Lloyd Kahn], it hasn’t happened and we need to stop lying to ourselves that it will. Live the life that fits your values, but don’t mistake that for changing the world.

Far too much of the debate about sustainability still orbits around ideas of smallness, slowness, simplicity, relocalization that often obscure the reality of our lives from us. [pullquote]Their main virtue is that they make incredibly complex systems that we cannot change alone seem susceptible to easy understanding and quick transformation through personal choice.[/pullquote] In other words, they let us deceive ourselves in ways that are extremely comforting.

We need to be better than that. We need to be bigger than that. We need to understand that a bright green future will look like nothing that has ever come before, and will involve us changing the fabric of our lives, not just the ornament. It will involve needing to be more connected to global networks of people working towards change, more committed to seeking understanding and transparency in complexity, more engaged with systems that make us feel small — because we are small, and the world is complex, and we can’t do this alone.

We’re redesigning our civilization. We need to be people who are tackling the most important systems around us, employing tools that can change them quickly at scale. We need to get comfortable talking policy, working in parallel collaborations, thinking in systems, understanding infrastructures and markets and flows, and using money to power comprehensive transformations.

The opposite of democracy is depoliticization. The idea that “regular” people can’t do this is insultingly elitist, psychologically isolating and inherently depoliticizing. Of course we can. Even those of us who lack formal education in these fields are entirely capable of contributing in important ways to big efforts — if we learn to think of ourselves as connected and collaborating, and start to pay more attention.

Ah, attention. Some will stop there and say, “people are lazy! they won’t pay attention to anything!” There’s some truth to that. We are primates are lazy, inclined to sit around, much sweets and groom each other. But we’re also curious, and passionate.

Many of us want to know how things work around us. Many of us feel passionate about the need for change. The simple hard reality is that the powers that be are incredibly effective at working to disillusion us, to make us too cynical to act in our own best interests, so overwhelmed by jargon and bureaucratic process that we get bored and go home. We are apathetic and disengaged in some very large part because that’s the way some people want us to be. That’s a hard truth, but still truth.

The answer to that apathy and disengagement is not to demand less from people. That hasn’t worked. Instead, I think, we need to regard not being boring as one of our cardinal design principles. We need to make change interesting, and fun, and provocative, and full of good times and relationships with others and meaningful work. We need to approach complex, vast systems in terms of art, and game design, and public festivals every bit as much as in terms of reports and committees and NGOs. We need a cultural movement, for sure — it just has to be a cultural movement aimed at making systems geekery a passionate part of the lives of regular people.

That, ultimately, is the biggest problem with the hand-made approach to sustainability: even when it works, it makes us passionate about small things in our lives, not engagement with the world. Visiting a neighbor’s great backyard garden may well encourage me to want to grow my own; it doesn’t encourage me to understand global agrobusiness, connect with food policy activists and do something to change the $2,000 in destructive agricultural subsidies the U.S. government pays with part of my taxes every year. The hand-made can be beautiful. It can be deeply personally meaningful. I’d like a world where the hand-made abounds. But the hand-made is not The Revolution.

*****************

And here is my response to Alex and other readers. The first three lines seem a little out of context but it picks up from there…

Yeah, fascinating. A fellow espoused the same view to me at a dinner party about six months ago [that the world was already so far gone there was absolutely nothing individuals could do] and I lost my temper with him, wondering aloud why he bothered to wake up in the morning. I countered with intentional communities, local food and something about mothers being the great saviours of the universe. But I couldn’t forget his words and wondered why they kept gnawing at me. When I read your post it all came rushing back in technicolor. It also reminded me of a quote I couldn’t stomach or wasn’t able to grasp for a long time: “Give everything away and follow me”. Not to liken you to J or anything 🙂 but what you suggest has a similar go/no go urgency – that environmentally we’re going to hell in a handbasket – and that one either a) believes this to be true or b) believes this to be false. I don’t see much room for a sorta/kinda middle ground.

So as I clean my house for the millionth time, pick up the plastic bits of my children’s toys, study for midterms, bring the winter clothes up from the basement, do the volunteer work, check on the in-laws, prioritize the house repairs, get the snow tires on the van, rake up the leaves, clean the gutters, and get over a house full of the flu, I have trouble seeing how it is possible for me to affect change on a meaningful global scale without dispensing with virtually all the trappings of our modern culture and social system. I’m personally finding it hard to Save the World in my spare time.

I think J had it right – along with other spiritual teachers and mystics – that we need to profoundly shed much of what we hold to be true in order to move forward. Our old model is broke and we need a new one, quick-like.

So with middle-age firmly upon me and the precious days zinging by ever more-quickly, I tell my four young kids and easily-shockable husband that whatever fits in the yurt, goes in the yurt. I say this often enough so that the “House For Sale” sign on the front lawn will not come as a surprise nor will the mountains of goods on the sidewalk labelled “Free to a Good Home.”

Shocking? Maybe. Terrifying? Definitely. But I just can’t seem to visualize my role in the big picture while I’m blinded by the pursuit of The American (sic) Dream. Or exhausted from cleaning up after it.

POSTED BY: ANDREA CORDONIER ON 3 NOV 09