I love riding New York’s subway system – just not as much as I love walking the city.

Riding necessitates paying attention to lines and stops and tracks – my mind can’t wander for fear of ending up in who-knows-where – but walking favours mental and corporeal freedom, especially when time holds no sway.

However, my penchant for perambulation has its downside: walking New York means I’ve all but missed the MTA Underground Art Museum, an Ali Baba-on-steroids-sized treasure trove.

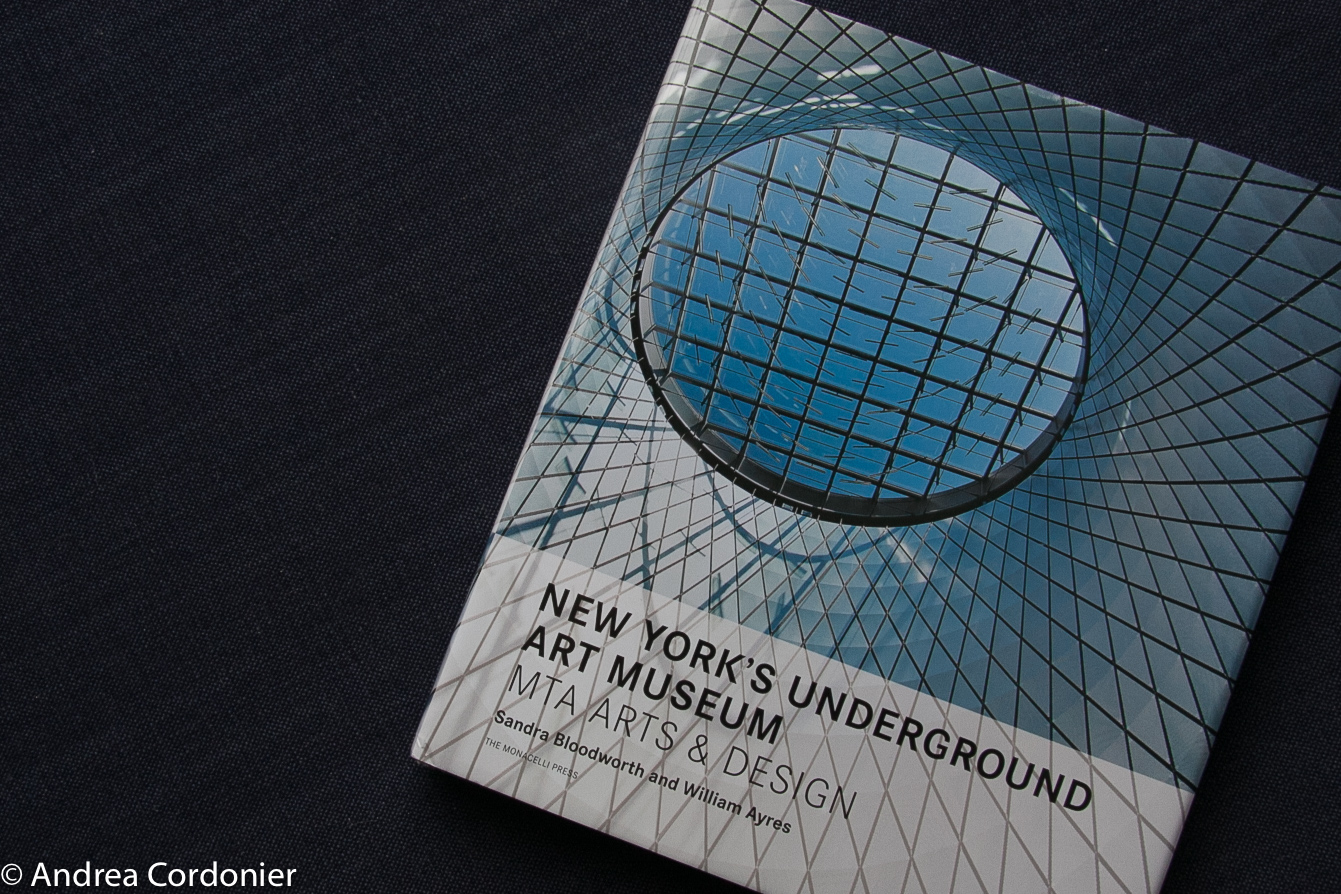

Lucky for me, this showed up under the Christmas tree.

Unlucky for me, I missed the historic opening of the Second Avenue subway extension, with its three new stations – and exemplary art installations – by a month.

Beginnings of the New York City Subway System

New York City’s first official subway system opened in Manhattan on October 27, 1904. The Interborough Rapid Transit Company (IRT) operated the 9.1-mile long subway line that consisted of 28 stations from City Hall to 145th Street and Broadway, quickly expanding service to the Bronx, Brooklyn and Queens. Amalgamation of competitors occurred in 1940, the New York City Transit Authority (NYCTA) was created to take over subway, bus, and streetcar operations from the city in 1953, and it all landed under the state-controlled Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA) in 1968.

Evolution of MTA Arts & Design

By the early 80’s, the city teetered on bankruptcy, its public transportation system the poster child for urban decay. That began to change with an injection of $18 billion for subway rehabilitation and the creation of MTA Arts & Design – a visionary move during a difficult time – to oversee the creation and installation of permanent artworks throughout the New York City transit system, Metro-North Railroad, Long Island Rail Road and the bridges and tunnels of the five boroughs.

From the beginning, the aesthetics of New York’s subway system were intended to be as important as the functional:

The juxtaposition of the words “art” and “underground” may seem anomalous, but in New York City the two have gone hand in hand ever since the earliest days of the subway system. William Barclay Parsons, chief engineer for the fledgling undertaking, insisted that the construction documents specify that the stations be designed, constructed, and maintained with a view to the beauty of their appearance, as well as to their efficiency.

The earliest works made use of a variety of ceramics including white glass tiles, brickwork, terra cotta and tesserae (small tile pieces) to create a mix of simple and complex name plaques, which identify many stations.

MTA Arts & Design is integrated with the MTA’s Capital Program. The MTA chooses a group of stations to be renovated during each five year period then allocates 1% of construction project budgets to the MTA Arts & Design to commission permanent works of art and restore its historic decorative elements, a virtuous funding circle.

But what began as a mandate for art commissioning and installation has expanded to include advisory services on the broader ridership experience: signage, lighting, materials, fare control areas and the design of new transit cars. Staff members provide input on the visual surroundings of stations and on system-wide issues like water mitigation and street furniture design.

The Growing MTA Underground Art Museum

In 1995, there were 48 new permanent artworks. Today, there are more than 300 permanent installations by world-famous, mid-career and emerging artists under the Percent for Art as well as a variety of commissions and events under five innovative umbrellas:

Music Under New York

Graphic Posters

Poetry in Motion

Digital Arts

Lightbox Project (Photography)

As many as 50 projects can be underway at any given time.

According to the MTA Arts & Design, one of the early learnings was that to be effective in a busy public environment, a work of art must be strikingly visible, call attention to itself, remain colour-fast over time, and be rendered in materials that withstand hard use, vandalism and cleaning.

Each piece is site-specific, fine tuned to the needs of its environment, determined in consultation with station architects and designers, reflective of the neighbourhood – its culture, history, diversity and built landmarks – and a link between passengers and unique places and spaces. Some projects are realized in partnership with a local institution, such as the American Museum of Natural History and Yankee Stadium.

For MTA artists, architects and designers, the exposure is unparalleled: more than eight million pair of eyeballs view their works every day.

And, in this case, three hundred eyeballs stare right back.

Like my ongoing “collection” of Guastavino tile around New York (and elsewhere), I am itching to explore more of the MTA underground art museum. This round, I had to be satisfied with discovering my first few pieces.

Oculus, 1998 (Andrew Ginzel & Kristin Jones)

Oculus is located in passageways under the World Trade Center and was largely untouched by the events of 9/1l. Oculus will also be visible at the Cortlandt Street Station after construction is completed. Jones and Ginzel’s work consists of over 300 unique mosaic renderings that use the oculus – the eye – as the central symbol. In their words, “Oculus was created to personalize and integrate the stations. Eyes are both subtle and strong – they engage passing individuals, allowing for meditation or inviting dialogue.” The eyes are from the artists’ photographs taken in New York , which were selected for the diversity of the subjects’ eyes. An enormous central eye set in the floor, grounds the composition and serves as the centerpiece of a map of the world which radiates outward.

I emerged from underground at Ground Zero looking for the other oculus – Calatrava’s World Trade Center Oculus – a combination public monument, transit station (PATH), high-end shopping mall and selfie-magnet that’s generated more than its share of press this year. While not an MTA build or installation site, the building, in (sort of) the shape of a dove, is impossible to ignore.

Inside, I felt like Jonah in the belly of the (beautiful) whale.

Next stop was the Fulton Center, just a few blocks away.

Sky Reflector-Net, 2014 James Carpenter Design Associates, Grimshaw Architects, ARUP

Sky Reflector-Net is an integrated artwork by James Carpenter Design Associates, Grimshaw Architects and ARUP, designed specifically for the Fulton Center. The monumental sculpture embraces light and air, creating a distinctive focal point within Lower Manhattan’s urban fabric.

Suspended within the atrium’s conical form, Sky Reflector-Net is composed of 112 tensioned cables, 224 high-strength rods and nearly 10,000 stainless steel components. Attached to the soaring cable-net are 952 perforated optical aluminum panels that distribute year-round daylight and bring the sky down into the lower levels of the Center. The artwork combines beauty and function, reduces energy consumption by 30 percent and powerfully connects the 300,000 daily transit users with a sense of daylight that will be constantly changing.

Visible from the corner of Broadway and Fulton Street, Sky Reflector-Net acts as a primary defining element for the Fulton Center –the powerful influence of natural light on our concept of the time of day, on the changes in the seasons, and the passing of years. It also is a key element in the creation of a renewed sense of place for Lower Manhattan.

This installation, also at the Fulton Center, is, by comparison Sky-Reflector-Net’s poor cousin and probably doesn’t get the love it deserves. I missed Anne Spalter’s excellent digital installation New York Dreaming because I didn’t know it was there.

I took the tram to Roosevelt Island to see Louis Kahn’s work, but stumbled across this MTA piece, Convex Disk, by Robert Hickman. It is composed of almost half a million hand-cut and reassembled glass pieces.

Recommendations for Viewing the MTA Art Installations

- For the best chance of catching the artworks, especially in large or complex stations, read ahead here and here and make note of the lines/platforms where they can be found. It’s possible to be in a station but not immediately spot the work(s) or not to find it at all, especially if you don’t exactly know what you’re looking for.

- Go it alone if you can’t find a suitable treasure-hunting partner. In some stations there can be a crowd enjoying the pieces/environment making it a pop-up social hub, a great place to meet like-minded people. Save yourself the pain of dragging someone along who’s less than excited about the adventure.

- Buy an all-day Metro Pass and ride at off-peak hours for more freedom to ogle without interrupting commuter flow.