I don’t know how to say this delicately so I’m just going to say it: my kid has pinworms. So if one of my kids has pinworms, chances are all six of us have pinworms. We will be extending no invitations for sleepovers anytime soon. Here’s why.

I don’t know how to say this delicately so I’m just going to say it: my kid has pinworms. So if one of my kids has pinworms, chances are all six of us have pinworms. We will be extending no invitations for sleepovers anytime soon. Here’s why.

Pinworm infection is incredibly common, occurring in about 50% of school/daycare age children and their caregivers and people living in institutions. The graphic epidemiological details are here. Treatment is a single dose of mebendazole, pyrantel pamoate, or albendazole, followed by another two weeks later.

Taking the medication is no biggie, but ridding your home of the worms and their eggs, which can live for two to three weeks each cycle, is almost as daunting as getting rid of bedbugs.

Infected people should comply with good hygiene practices such as washing their hands with soap and warm water after using the toilet, changing diapers, and before handling food. They should also cut fingernails regularly, and avoid biting the nails and scratching around the anus. Frequent changing of underclothes and bed linens first thing in the morning is a great way to prevent possible transmission of eggs in the environment and risk of reinfection. These items should not be shaken and carefully placed into a washer and laundered in hot water followed by a hot dryer to kill any eggs that may be there. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

The calculations for daily laundry and housework for four weeks make me crabby: 5 beds/sets of sheets to change and wash; clothes; towels; disinfecting bathrooms; vacuuming, etc. Double expletive. And this cycle will reoccur if reinfection occurs.

I wondered whether the root of the infection was our guinea pigs or cats. I asked our vet if cross-species infection of pinworms was possible. She said she’d seen literature that suggested it was, but had not witnessed a direct case herself. Online, many sources, including the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, indicated that pinworms could only be transferred through human-to-human contact,

So if pinworms don’t make the jump, then what do?  BBC News reports that leading scientists have warned that “animal diseases could be the biggest threat to human health in the years ahead,” with “around 75% of emerging diseases in humans coming from animals, including AIDS, Bird Flu and West Nile Virus.” Urbanization, globalization, changes in animal farming practices, and ecological disruption contribute to the mutation and transmission of animal-based diseases.

BBC News reports that leading scientists have warned that “animal diseases could be the biggest threat to human health in the years ahead,” with “around 75% of emerging diseases in humans coming from animals, including AIDS, Bird Flu and West Nile Virus.” Urbanization, globalization, changes in animal farming practices, and ecological disruption contribute to the mutation and transmission of animal-based diseases.

A 2007 Nature report entitled Origins of Major Human Infectious Disease offers a fascinating exploration of the subject. Virologists Nathan D. Wolfe, Claire Panosian Dunavan and Jared Diamond conclude that the bulk of animal-borne infectious diseases emerged in the Old World in the last 11,000 years, in tandem with the rise of agricultural-based societies.

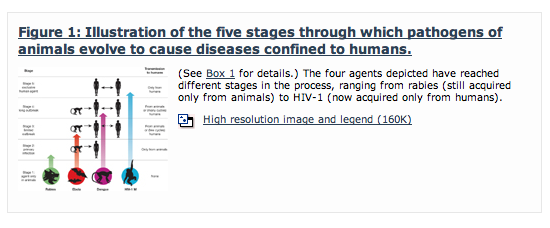

Not every animal-borne pathogen can make the leap to the human population, or remain there, due to a number of factors that influence their “persistence.”

Not every animal-borne pathogen can make the leap to the human population, or remain there, due to a number of factors that influence their “persistence.”

The researchers studied 25 different diseases, 15 found in ‘temperate’ climates (like Canada) and 10 distinctly tropical, selecting these diseases for their high mortality rates. They found that the temperate diseases were: less likely to be conveyed by insects; more likely to convey long-lasting immunity; that a “somewhat higher proportion” made it up to Stage 5 (human to human infection); that any resulting death would be short and painful; and that most of them were crowd epidemic diseases. This means that the disease would make its rounds very quickly, kill off its victims or create immunity, and then exhaust itself in the defined population, effectively dying out. However, the more populated an area, and closer in proximity to other populated areas, the longer the disease would replicate.

Out of the fifteen temperate diseases studied, likely eight came from domestic animals and three from apes or rodents. The remaining have no known origin. As populations grew, so did the need for more domestic animals. Increased human/animal contact accompanied that need, offering much more than hunters/gatherers would have experienced in the wild. Almost all of the animal-derived pathogens originated in other warm-blooded vertebrates (mammals). Two bird-based pathogens were the exceptions.

Almost all of the twenty-five pathogens originated, or likely originated, in the Old World. Chagas disease (tropical) came from the New World while the origins of syphilis and tuberculosis remain unclear. And anyone familiar with New World history knows exactly what happened next. The invading Europeans were resistant to their familiar diseases, while the local native populations were decimated. According to the researchers, there was no equivalent New World ticking time bomb awaiting the conquerors.

This pathogen-imbalance directly correlated to the presence of livestock. Thirteen out of fourteen species of domesticated livestock originated in the Old World, including the omnipresent cows, sheep, pigs, goats and horses. The llama was the sole New World exception, but it was not milked, ridden, hitched to ploughs, cuddled or kept indoors, drastically curbing the amount of hands-on human interaction.

The researchers concluded this paper stating that there was “no ongoing systematic global effort to monitor for pathogens emerging from animals to humans.” But Dr. Nathan D. Wolfe went on to found the Global Viral Forecasting Initiative (GVFI), which works to do just that. Here’s a TED video that describes the initiative:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=T1qJ-GF7_UY

For now our climate warms, our populations grow and disperse, and we probably eat more meat than we really need to or should, even when we have alternatives. Kind of feels like a ticking time bomb, doesn’t it?