In setting forth different principles, I shall mainly be writing about common, ordinary things: for instance, what kids of city streets are safe and what kinds are not; why some city parks are marvellous and others are vice traps and death traps; why some slums stay slums and other slums regenerate themselves even against financial and official opposition; what makes downtowns shift their centres; what, if anything, is a city neighbourhood, and what jobs, if any neighbourhoods in great cities do. In short, I shall be writing about how cities work in real life, because this is the only way to learn what principles of planning and what practices in rebuilding can promote social and economic vitality in cities, and what practices and principles will deaden these attributes. ~ Jane Jacobs, The Death and Life of Great American Cities, 1961

Back in May, I lucked into being in New York City during Jane’s Walk, the annual neighbourhood walking event held in cities around the world. It’s named in honour of Jane Jacobs, the celebrated urbanist, activist, and writer who established herself first in Greenwich Village, and then in the Annex neighbourhood of Toronto. While I caught a couple of the walking tours (Park Avenue and Manhattan Civic Centre), I didn’t make it to the village, to the pilgrimage site of her former home at 555 Hudson Street.

This week, Jane’s neighbourhood was my unfinished business and a Google maps walking tour my guide. I wish I could say I discovered the area as something more than a tourist, but that’s what I was, poking around to get an initial sense of the shape of the place.

I walked (of course) from E.61st down to 14th, via W.11th and Hell’s Kitchen. The torrential downpour slowed, and then stopped, by the time I joined the High Line at 30th. At Hudson I stripped off my raincoat, sweating in the summer-like heat and humidity.

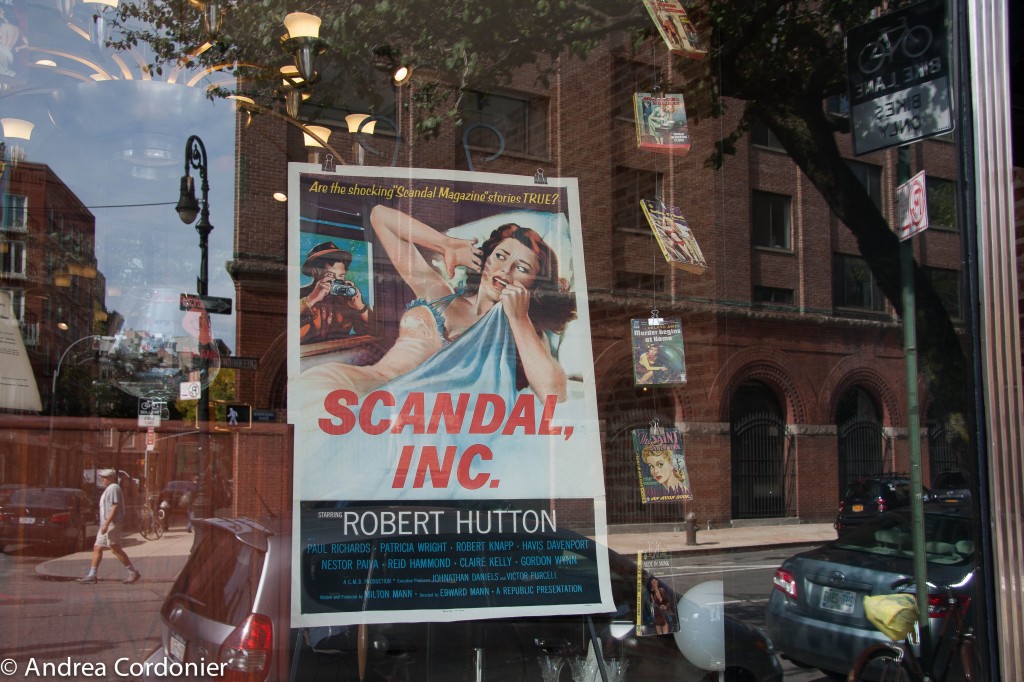

At midday the streets were mostly sleepy, dotted by women-of-a-certain-age and their tiny dogs taking lunch at streetside tables and benches. A solitary man in sunglasses and his shaggy pooch ruled over the sun-soaked patio of the iconic White Horse Tavern, traditional haunt of longshoremen and poets and writers like Dylan Thomas, Jack Kerouac, Norman Mailer and Anais Nin. A few blocks on, a crew shot a television series, crowding the sidewalk with imaginary activity. High sun and deep shadows framed the sidewalks; every hour or so the spotlight would shift, illuminating a different person, place or thing. By dinner time, the bright orange rays beamed low and magically along the east-west axis and the sidewalks teaming with people of all ages: suited men whisking uniformed children home from school and day care, office workers picking up groceries, college students taking advantage of happy hour prices, elegant high-heeled women rushing home from work.

Greenwich/West Village ranks as some of the most expensive real estate in the United States. The inevitability of gentrification has priced it out of the hands of everyone but the very wealthy or those lucky enough to benefit from rent controls. I can understand the attraction of the place. The scale remains intimate, human, the roads organic, confusing and enviously leafy, brick townhomes uniform yet eclectic, all molded by history. Everything is at hand: There are restaurants, taverns, shops, churches, schools, pocket parks, public transport, and the river. Charming, pretty, yet solid, it’s a fairytale village where communion with other souls seems possible. And all in the heart of a city of eight-and-a-half million.

Jane’s former home is plain painted brick, two floors over vacant retail space and, at this moment, burdened by scaffold. In quick succession, it has recently housed a specialty baby shop, a seller of glass wear, and a purveyor of ladies clothing. One has to sell a lot of chotchkes to make the pricey rent, never mind a reasonable living. Unfortunately, it’s the predictable, vanilla chains that can afford this, simultaneously putting dollars in the jeans of landlords while chiselling down the rough edges that lend neighbourhoods their uniqueness and real interest. It’s not exactly what Jane envisioned back in 1961 when she rallied for the preservation of old (old, low-rent and therefore useful vs. old, fancy, expensive) buildings in her famous treatise The Death and Life of Great American Cities.

I felt the urge to genuflect on her doorstep, but settled for taking coffee in the adjacent cafe and effectively becoming a pair of her famously-invoked eyes on the street. How’s that for life imitating art?

I wandered for several hours photographing to my heart’s content before ending the afternoon with a glass of wine and some charcuterie at the delicious and artfully-styled Buvette. Then I hoofed it back uptown in the day’s remaining light.

3 responses to “Walking Jane Jacobs’ Hood”

[…] I explored her ‘hood in New York’s Greenwich Village last year, I needed to visit her former home in Toronto’s Annex to complete my journey and […]

Such beautiful images. It makes me want to return, do that walk.

Trust me, I thought of you every step of the way!